The holy trinity of Prostitution, Love and Capitalism

Peter Breedveld

“All work is prostitution”, writes Okazaki Kyoko in the afterword of her graphic novel Pink. “Then again, all work is also love.” But love, in Tokyo, is not generally something people comfortably talk about. “Therefore it is like a horrifying monster, and so is capitalism”, Okazaki states.

Prostitution, capitalism and love form a holy trinity in Pink, which was first published in 1989, not long before the economic bubble burst. Before that happened, Japan was seen worldwide as an economic miracle, admired and feared, and hated. It was the time Japanese people where the villains in many popular American movies, like Ridley Scott’s Black Rain and Philip Kaufman’s Rising Sun.

Pink plays inside that bubble, when happiness came in the form of things you could buy. Louis Vuitton handbags, Armani clothing, the company of a woman. Or a man. One of the protagonists in Pink, Yumi, is an office worker who works as a call girl on the side, to be able to buy expensive stuff and to feed her crocodile.

Free captive animal

She keeps a crocodile in her bathroom. The captive animal seems to symbolise freedom for her, to be found in the jungle it’s from. Yumi is not free, but she buys her freedom in the form of a symbol, and that symbol is a free animal from a free place, imprisoned in a tiny bathroom. Yumi holds herself captive too, in a prison of expensive stuff.

She is a prisoner in the office where she works, surrounded by the babbling of her colleagues, who humiliate her now and then, reminding her that she ends her working day awfully early (almost a mortal sin in Japan) and that she delivers sloppy work. But as a prostitute she is free. Free from guilt, from the judgments of her fellows, master of her own sexuality. Her clients treat her with respect, although she has to listen to the fatherly speeches of one of them, warning her that she can’t live like this forever, that she will have to find herself a husband to take care of her.

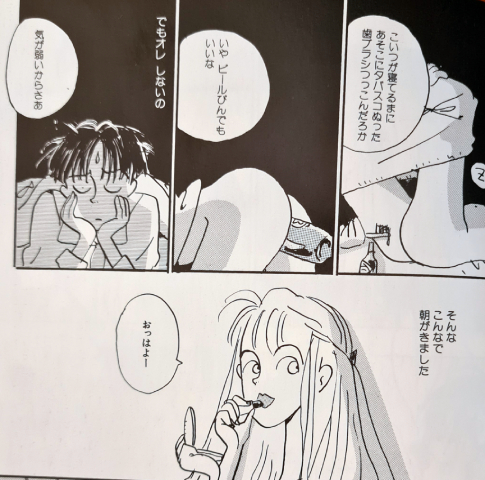

Love comes in the form of another lost soul, a university student, Haruo, who used to have a hundred ambitions, but can’t seem to get himself into gear, so he found himself a sugar aunt, who is Yumi’s stepmother. He captures Yumi’s attention in a hotel where she just leaves one of her clients, and where he parts with her stepmother. She follows him to his home and they start dating. After a few nights he wakes up alone in her bed and is cornered in her bathroom by her crocodile. Yumi’s younger half-sister turns up and threatens to let the crocodile eat him, unless he writes a brilliant story for her, which he does. Or anyway, she thinks it’s a brilliant story.

Famous novelist

So now he decides to become a writer and write a novel. But he doesn’t want to put too much effort in it, so he composes his novel by cutting up the work of other writers and rearranging the fragments into a whole new work. Next thing you know he wins an important literary prize and is a famous novelist.

But the mother he left for her adoptive daughter wants revenge for the fact Yumi stole him from her and for the fact Yumi has youth and her own beauty is fading. So like the stepmother in Snow White she tries to poison her with apples. An apple pie, to be precise. Which ends up only inducing her period but it kills her crocodile, which the stepmother turns into an expensive suitcase and sends her as a cruel present.

Only as I’m writing this, I fully realise how philosophical and poetic this graphic novel truly is. It’s not in the musings of Yumi and the other characters in Pink, which appear to me to be slightly incoherent streams of semi-consciousness, although stuff might have gotten lost to me since I read Pink in Japanese and my Japanese reading skills are… shaky.

I picked this up in a warehouse in Tokyo. Pink is a pretty famous graphic novel but I had never heard of it. I choose it because of the incredibly dynamic drawing style, a kind of graphic short-hand, quick and sketchy and energetic, but elegant, with sensuous lines. And it seemed to be about sex and it was by a woman. Later I found out I had already been introduced to Okazaki’s stories, for the movie Helter Skelter, an absurdistic indictment to the beauty industry by one of my favorite directors Ninagawa Mika (also a woman) is based on a graphic novel by Okazaki, as is the movie River’s Edge by Yukisada Isao.

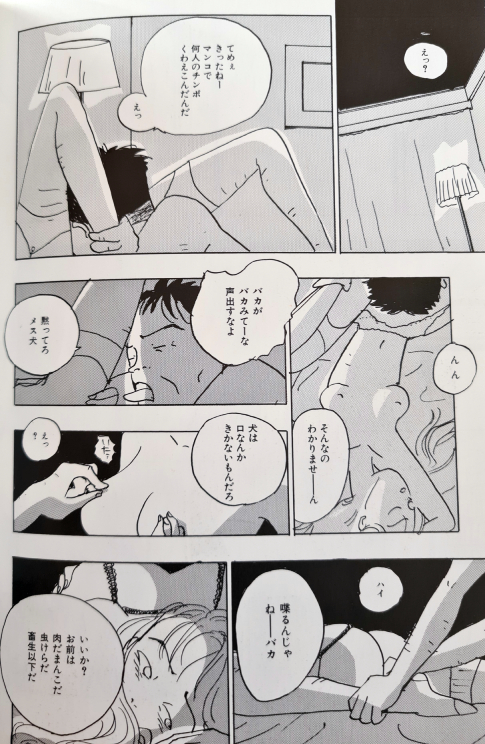

The sex, or sexuality, is wonderfully free and candid in Pink. Okazaki doesn’t bother with strict divisions between prostitution and love-sex, although Haruo seems to be bothered for a while by bouts of vague jealousy, which are quickly dismissed by Yumi. When the media find out this newly famous novelist lives together with a prostitute, they pester him about it but he can’t be bothered with it, not with their questions and not with the shame society wants to impose on him, which is a novelty the journalists wholly appreciate.

Japanese manga famously can’t have genitalia or pubic hair depicted in them, but Pink has lots of it, which puzzles me a little, but I guess the short-hand style of drawing propably misled the censors so it stays hidden in plain sight.

Pink has been translated in English, as has Helter Skelter. You can order them, for example, here.

Please support this website:

boeken, Peter Breedveld, strips, 24.03.2021 @ 16:37

RSS

RSS