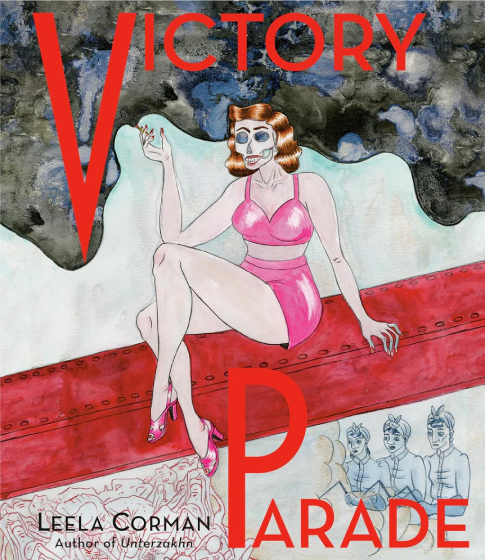

Sisters are doing it for themselves in Victory Parade

Peter Breedveld

With all the able-bodied men gone to fight the Nazi’s in Europe, two Jewish women and a girl manage quite well in wartime New York in Leela Corman’s new graphic novel Victory Parade. Rose Arensberg lives with her daughter Eleanore and a refugee from Germany she has taken in, named Ruth. Rose works in a factory where most of the workforce is replaced by women and, awaiting the return of her husband Sam, she has taken a lover, a one-legged veteran from the Great War.

She tells him Sam was her high school sweetheart and that she had ambitions until she got pregnant with Eleanore. “Gunish helfn, as you know”, she says. And then: “Or maybe you don’t.” It’s not the same for men as it is for women.

Ruth, whose last name isn’t mentioned as far as I can remember, has a fire burning in her. It’s not hard to guess why, with her entire family wiped out in the European extermination camps. She works a a waitress and beats up a customer harassing her, drawing the attention of an old man who is impressed by her strength and vigor. He offers her a job as a female wrestler in a club he runs. She excels at it an becomes the audience’s favorite villain in the ring, ironically being mistaken for a a German Nazi, “fresh from the U-boat”. She becomes known as Ruthless Ruby the Killer Kraut.

Tortured soul

Wrestling seems to be the only possibility for Ruth to get intimate with other people, her opponents, whom she gives glimpses of her tortured soul while she publicly humiliates them. One of them she holds very tightly to her while she says: “I hate the sound of my own heart beating.”

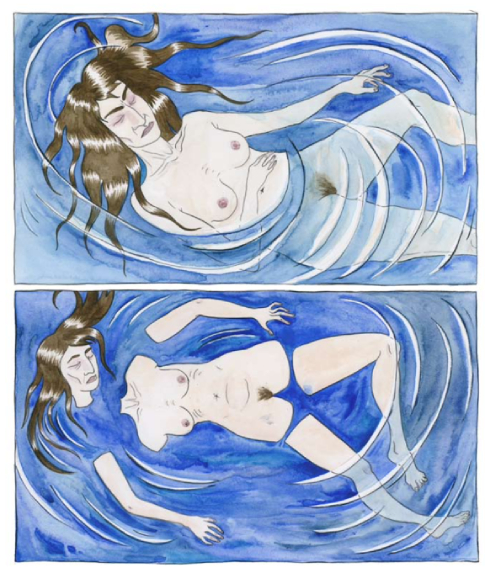

Alone at night she sees her dead mother, who tells her she and her husband fled from Poland to Germany which she thought an enlightened place. Her mother appears to her in visions during her fights in the ring too, to tell her she may not join her in death yet. She has to live until she dies.

Her memories of Germany are delirious hallucinations. To depict them, Corman uses paintings from the interbellum period by the likes of Oskar Schlemmer and Otto Dix. It’s funny how Corman, when the action takes place in the US, draws from popular culture, American wrestling and musicals and such, in Europe it’s German Expressionism and Bauhaus. What the Nazi’s came to designate as Entartete Kunst.

The two come together in Corman’s own art, clearly inspired by German expressionism but also, I think, by painters like Marc Chagall. American comics are obviously an inspiration too. Corman often mentions the Hernandez brothers as an inspiration. Indeed in Jaime Hernandez’s Love & Rockets stories female wrestlers are an important motive.

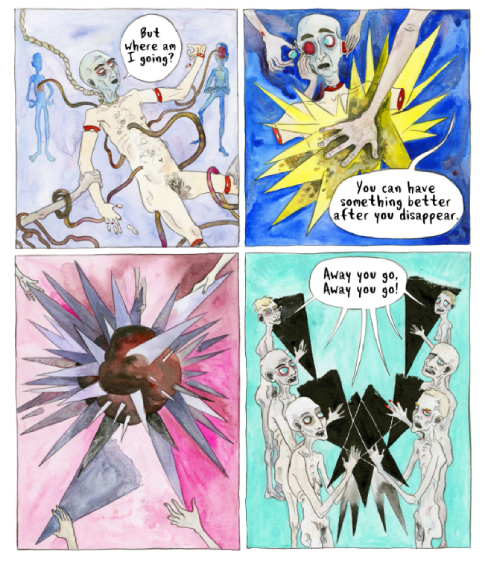

Revenge fantasy

American pop culture and interbellum art are merged in the feverish conclusion of the book, in a sequence which is as inventive as it is provocative. Maybe it’s the most provocative treatment of the Shoah we’ve seen since Art Spiegelman’s Maus. I don’t want to give away too much, except that it’s a brilliantly delirious but also very morbid revenge fantasy.

Reading the description above, the reader will probably think Victory Parade is dark and heavy. It is, and at the same time it is not. At the same time you could call it light reading about heavy subject matter. There’s a dark humour and also a vivid fierceness, an unstopable energy. Corman doesn’t so much combine these opposites as let them flow into each other. She does this with everything. For instance, her work is always very physical, but at the same time it’s very much about the mind, about how everything happens in the characters’ minds. Everyone in Victory Parade is constantly hallucinating, but it’s always about bodies and body parts. The two are inseparably intertwined.

Corman also somehow removes the line between the repulsive and the erotic. This struck me in her previous book, Unterzakhn, and it’s also very apparent in this one. Corman looks and finds the erotic not in the idealised fantasy, but in the very earthly human flesh that you can almost smell on her pages.

Dark irony

Corman doesn’t like divisions. She’s a non-binary by nature. In an interview I read somewhere she says something like she doesn’t like to talk about masculinity and femininity. Now there ’s a clear disctinction between males and females in Victory Parade, and at the same time there is not. During the war it becomes clear women take over their absent men’s roles rather effortlessly.

In the same vain you could consider the title of the book, Victory Parade, as darkly ironic while at the same time it is emphatically not.

In this review I can only hope to have scratched a little of the surface of what Victory Parade is about. It’s a book I discover something new in every time I open it. Every time I look at a page. Her pages you could hang in a museum seperately, out of their context they get a meaning of their own. It’s a multi-layered book, bursting with ideas and observations, caleidoscopic, visionary, beautiful, ugly, light, heavy, prosaic, poetic, cruel, full of love. All of those things and much more.

boeken, Peter Breedveld, 31.05.2024 @ 12:17

RSS

RSS