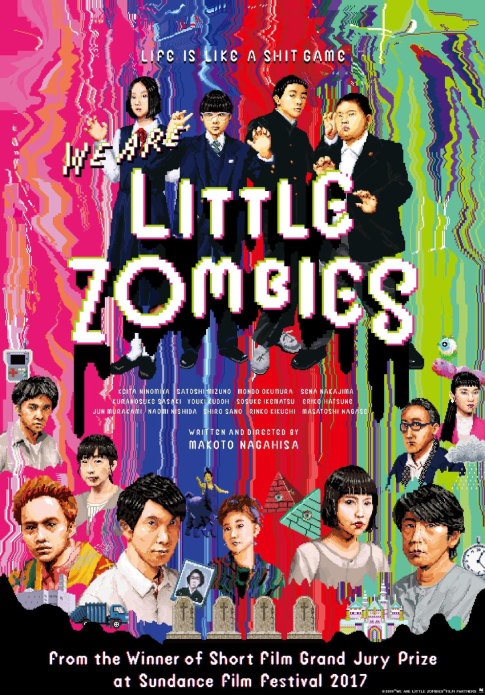

No crying for your dead parents in We are Little Zombies

Peter Breedveld

Zombies are not my favorite and I don’t like cutesy children’s takes on grown-up themes, so I am ashamed to say I skipped Nagahisa Makoto’s We Are Little Zombies when it was featured at last year’s Camera Japan film festival in Rotterdam, because of the title alone.

But by chance I saw the movie last week and it turned out to be one of the most entertaining, innovative, emotionally satisfying and visually rich cinematographic efforts I’ve seen in a while. Also, We Are Little Zombies is a very mature approach of the theme of grief, an astute observation of what it is to be young in this age, while it also tackles a whole range of social and existential issues on the way.

In short, this movie is really deep.

It took me a while to get into it, though. It begins with the main character, 13 year old Hikari, a dorky boy with owlish glasses, describing the ashes of his dead, cremated parents as the grated cheese on a plate of spaghetti Bolognese, during which a crude cut-out image of grated cheese being sprinkled on a plate of pasta is shown. Then we jump back in time, when Hikari is called to the morgue to identify his parents, who died in a traffic accident as the passengers of a tour bus. He imagines being the victim of a prank set up by the morgue people and his parents, who rise up from their hearses to surprise and reassure him that everything is alright. But it’s all a fantasy, his parents are really dead.

Unsettling experiences

I found this light treatment of a serious matter too forced and was about to give up, when the movie directed its attention to Hikari’s new friends, all 13 year olds, whom he meets at the crematorium and who are also freshly orphaned. The stories of their parents deaths are more intensely told, with much bolder imagery, which result in unsettling experiences. We see the toughened Takemura, whose parents committed suicide, take on his father who abuses his mother, and get the shit beaten out of him, while in the adjacent room his older brother and his friends are playing a punk-rock song, and a very good one, too.

The easy-going parents of easy-going Ishi died when their restaurant was destroyed by fire. We see an old drunk in that restaurant doing a funky rap in which he philosophises about octopi having the intelligence of human three-year olds and how that affected his entire world-view. Again, a very good song. Ishi is having a good talk with his dad, who urges him to be strong by making his own decisions, which he himself regrets never having done.

Budding sexuality

But most disturbing is the story of Ikuko, a girl whose budding sexuality awakens the dark side in all the grown-ups around her. From her piano teacher, who is coming on to her, to her father, who inappropriately jokes about wanting to marry her. Director Nagahisa makes it all the more unsettling by showing us explicitly her vamp-like qualities, as if to make us understand why she attracts these sexual predators, as if to manipulate us into blaming her for it, and make us complicit in the exploitation of ths child. Her mother says she and her father would be better off without her because of this. It turns out she was right, because they are murdered by the piano teacher, after Ikoku told him that she wanted to be free of them when he asked what she wanted for her birthday.

The four kids are very stoic about their parents’ deaths. “Why aren’t you crying, are you dead inside?” Hikari is asked by his aunt. But he sees no use in crying. “Babies cry to signal they need help”, he says, “but nobody can help me now so there’s no point in crying.”

They go on a journey, which is depicted as an old-fashioned nineties computer game, complete with the primitive digital music those games had at the time. First they have to gather some items to be able to reach the next level of the game. Hikari picks up his out-dated portable game console from his parental home and a goldfish, which they set free in the river, Ishi salvages a wok from the remains of his parent’s restaurant and Takemura steals his brother’s bass guitar. They enter Ikoku’s house too, which is a crime scene, but it’s not clear to me what they take from there.

Social media

After an encounter with a group of homeless people, who give a great spiritual-like musical performance, another brilliant song, they decide to form their own band, Little Zombies, come up with a very catchy earworm of a tune (my son, who saw the film at a German festival, told me everybody was singing it the whole time in the bus back home: “We are little zombies, but a-live, we are little zombies, but a-live”), get discovered and become famous almost instantly. Grown-ups appear from all over to exploit the children and the crowds on social media turn up to hunt down the people they hold responsible for their parents’ deaths.

And then we’re only about half way this roller-coaster of a movie, which is brimming with so many story and visual ideas, socio-political commentary, existential philosophy, experimental cinematography and playful music that any lesser director would have turned it into a cluttered chaos, but Nagahisa keeps it clear and steady, keeping all these balls in the air like a veteran juggler.

Strong visuals

This is his first full-length feature film (he directed an award winning short film three years ago) but Nagahisa has ample experience as a director of music videos and commercials. As with many other Japanese directors, for instance Survive Style 5+’s Sekiguchi Gen, Nagahisa uses his gift to translate messages into strong visuals to make an aesthetically and narratively meaningful film. I hope We Are Little Zombies is the promise of many more films like this in the not too distant future.

Film Reviews, Japan, Peter Breedveld, 21.06.2020 @ 09:41

RSS

RSS