One another in Dokkum

Peter Breedveld

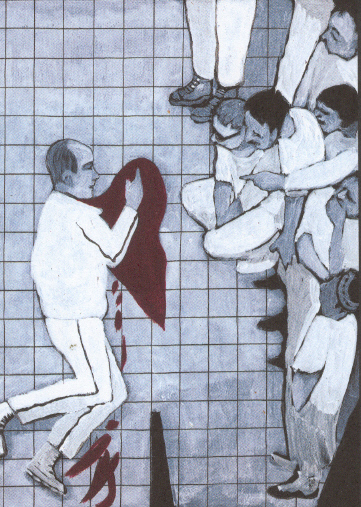

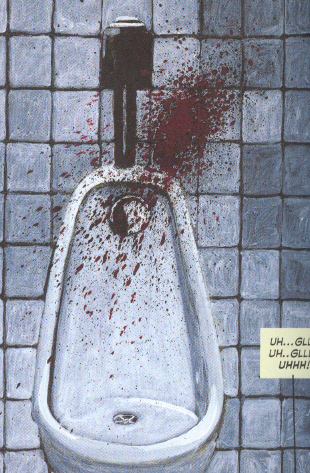

At the beginning of the new book by graphic novelist Guido van Driel, Om me kaar in Dokkum (One another in Dokkum). a man lays on the ground bleeding, after an attempt is made on his life. I don’t want to die. Not now. I am not ready yet’, he thinks as he feels his life flowing from him.

Elsewhere in the book the famous story of the Christian missionary Boniface is told. Boniface was murdered near the Dutch town of Dokkum in the year 754, after he had cut down some oaks which the Frisians considered holy. Caught by a blind frenzy they slaughtered Boniface and his companions.

It’s almost scary how the book reminds us of the terrible murder on filmmaker Theo van Gogh in November last year and the aftermath of that tragedy, although Van Driel started making it a full year before everything happened. Boniface reminds us of Van Gogh, who was murdered by a fundamentalist Muslim because of his film Submission, which he made together with politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali and is considered by many Muslims to be sacrilegious. Ever since, there have been high tensions between Muslims and non-Muslims in Holland, which was once considered as a haven of freedom and tolerance.

Let’s just agree that in both cases we are talking about a brutal and shocking murder, Van Driel (1962) reacts. But he does himself see the similarities between Boniface Van Gogh. Boniface, who tactlessly attacks those oaks with his axe, that is exactly what Van Gogh did. It is entirely wrong that someone is murdered for that reason, of course. But somehow it doesn’t seem that strange either.

Apparently Van Driel, who worked on his book for a year, has been very sensitive to the signs of the times. It is a time to be engaged as an artist, he remarks. He has had that feeling since the terrorist attacks in New York, more than three years ago now. Since the Van Gogh murder he is continually involved in a conflict with himself. On the one hand I have the feeling I have to do something. For instance, someone I know goes to all these debates all of a sudden. On the other hand I tell myself to not lose my head, to keep it cool.

Van Driel lives in an unmistakably multicultural neighbourhood in Amsterdam. Right after the murder he got into conversation with a group of Muslim boys. They said that the killer, Mohammed Bouyeri, should not have killed Van Gogh, but that he should have only beaten him up. They said they understood what motivated Bouyeri. Didn’t you see that movie?’ they asked me. ‘That woman with those quotes from the Koran painted on her naked body, don’t you think that’s terrible?’

These are disturbing comments, but there is no reason for panic, Van Driel thinks. I don’t get all these people who are saying they want to leave the country now. For Pete’s sake, people like that are certainly not going to save the country!

The title of his new book refers to an old popular Amsterdam song from the seventies, with lines like: We are on this world to help one another, to help the Spaniard and the Turk who live among us. Neighbourly love is the cork on which we all float. Terribly naïve, and also with a paternalistic touch, Van Driel thinks. But he didn’t mean the title as a cynical comment. Being cynical is to give up, he says.

Van Driel stays optimistic. What else can I do? Many people criticise the Amsterdam mayor Job Cohen, because he always says he wants to keep things together’. What alternative do those people have? Do they want Holland to turn into some kind of Northern Ireland?

Van Driel has been a darling of the critics for years now, but he’s mainly unknown to the large public. He made Om mekaar in Dokkum for the municipality of Dongeradeel, which also includes Dokkum. Twenty-seven panels from the book are enlarged and affixed as tableaux to the front of the new cityhall of Dongeradeel. The book has been used to promote the idyllic, historical city, situated in the rural landscape of Friesland, one of the two most northern provinces of Holland.

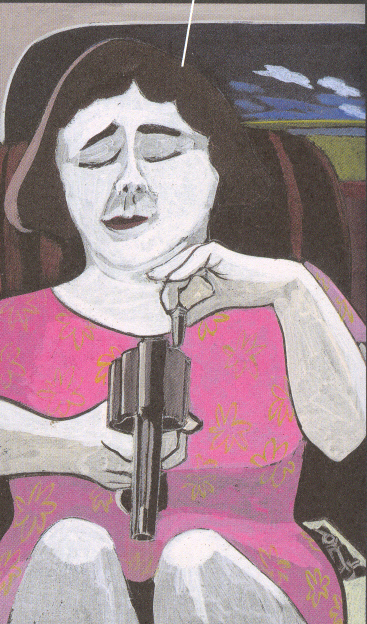

The main protagonist in the book is an Amsterdam criminal who survives an attempt on his life. Together with his bodyguard he goes to Dokkum to search for the man who tried to kill him. There’s a parallel storyline about a refugee from Angola who lives in an asylum seekers centre in Dokkum and who tries to get a residence permit.

“The asylum seeker gave me the opportunity to view the city and the local customs through the eyes of an outsider, Van Driel explains. I had also been working on a film script that didn’t work out about an Amsterdam criminal who has a near death experience, so I weaved that into the story too.

Apart from being a social commentary Om mekaar in Dokkum is also a plea for a less stressful way of life. After his near-death experience the criminal has turned into a different man, who tries to live life to the full. I have read a lot about near death experiences, Van Driel says. I read that people who have had them feel like their senses have been renewed. Their taste is more intense, their sense of smell has improved. Life comes storming at them.

Just as well documented is the conversation between the asylum seeker, his interpreter and the civil servant if the Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND). On the website of the IND I read something about the stock’ that the IND had to process. I find that appalling, that you talk about people in terms like that. I wanted to do something with that. I also used an article I had read about a Somalian refugee who had been so traumatised he did not want to talk about his past, thereby blowing his chances to get a residence permit.

Prejudice and xenophobia are the main themes in Om mekaar in Dokkum. I want to say something about our relationship with the stranger’, Van Driel explains. What is so threatening about the strange? Because even the people who are most near to us, are strangers in certain ways. That is good, there’s nothing scary about that. It is even pleasant and attractive. When you are in the least bit curious, I mean.

Not everybody in Dokkum was happy with the book though. A few Christian political parties objected to the municipality giving the book to relations as a present, because of the harsh language and bad manners of some of the protagonists. It caused a small riot which was followed by a lot of publicity for the book, which was also praised by the critics (as is wont with Van Driels books) as a literary masterpiece. The first printing has now been completely sold out and there are even plans to make a film.

Algemeen, 19.03.2005 @ 10:41

1 Reactie

op 21 03 2005 at 02:05 schreef Tom Thomas Maine:

Red ons van dit soort multiculturalistische simpele zielen .

RSS

RSS