You have to be careful

Peter Breedveld

Joe Sacco is a journalist who writes his stories in the form of comic strips. He went to Palestine in the early nineties to report about the Gaza Strip, which resulted in the book Palestine. Later he went to Bosnia where he visited a Muslim enclave in Serbian territory, described in Safe Area Gorazde. Last summer The Fixer (translated in Dutch as De Fikser) appeared, about Sacco’s dealings with a shady Bosnian ex-soldier called Neven.

Why do your journalistic accounts have the form of comic strips?

The thing is that after I finished my studies in journalism I didn’t find work that was inspiring. The first job I had was for a magazine about notaries, writing about stuff I had no interest in at all. After that I worked for a magazine that was really driven by it’s advertisers. When the ad people sold an advertisement, they would come up and drop a note on my desk saying that a certain restaurant had bought an ad and maybe we should write an article on this restaurant. That is not what I studied journalism for. At some point I had had it with this so-called journalism. So I started drawing comics as a way to have a satisfying creative life. I never really thought of it as a career but I thought I am going to see if I can make a living doing comics. And ironically I ended up doing real journalism in comics form.

Did comics give you the opportunity to do the kind of journalism you always dreamed of?

No. I saw an opportunity to do comic books. The kind of comics I initially did was humour, satire, maybe some non-fiction and I did some autobiographical stuff. It wasn’t until I had established an honest career -not a very great one, but one that I felt I was going to pursue for the rest of my life- that I thought I should do comics about things that were going on in the world. I wasn’t exactly sure what I was going to do. It was accidental. I had studied journalism and I went to the Middle East. And instead of doing straight autobiographical strips, I started to behave like a journalist. These journalistic notions came into my mind: I should interview this person, that person, I should collect some information about the cutting down of olive trees by the Israeli government, and so on. My training just kicked in naturally. And so, it was very organic. I didn’t have some grand scheme of doing journalistic comics. It just accidentally worked out that way.

Palestine has a very different feel from the book on Gorazde. Gorazde is much more journalistically focussed. I sort of knew what I was doing more with the Gorazde book. Palestine seems more organic. It has a good flow to it, but as a straight journalistic account Gorazde is probably more advanced.

Where does your fascination with war come from?

It’s just the circumstances. When I went to the Middle East I wasn’t thinking about war. I was thinking about the political problems there, which have a violent component. I didn’t think of it in terms of going to a war. After I had been working on Palestine, Bosnia seemed a logical next step to make. I figured, well let me see if I can write about the situation in Bosnia too. It’s not that I was interested in the sound of gunfire or anything. It’s because politically speaking I was disturbed by what was going on in Bosnia. That’s the reason to continue. In some ways it becomes a career, it’s almost accidental. I am known for my comics about wars now and that’s what people want me to work on, so there’s that component as well. But I’m only going to work on something that matters to me. I am not going to go to some place for the hell of it.

Why didn’t you go to Afghanistan or Iraq?

I was working on my book The Fixer. You cannot just drop what you’re doing and change gears. It takes a long time to do a comic book. You can easily scatter your attention and get caught up in the next thing. I’d rather not do that.

Why does Gorazde start with an account of the Second World War?

In World War Two certain atrocities were committed that, under the leadership of Tito weren’t discussed openly. So the people don’t know their history. Tito was trying to keep everyone from talking about the past, but that wasn’t a good idea because if people don’t know their history a politician like Milosevic can pour something into their head. You can be manipulated if you don’t know your history. It’s important to know what happened in World War Two because it has a big bearing on how people perceived what was going to happen in the early 1990’s. For instance there were great massacres of the Serbs, but the Serbs were also involved in massacres of the Muslims.

Why are you in your own comics?

Because I was doing autobiographical comics already. It was just natural to draw myself in the work. Because initially when I was going to do something about the Middle East my initial idea was to write about my own experiences. It began to have advantages for me. It’s clear to the reader that way that this isn’t some person…it’s almost like a pronoun; I’ve drawn myself almost like the word I’. It’s clear that the journalist is in there, he affects what’s going on, and he is affected by what’s going on.

You choose sides in your stories. Isn’t that very ‘un-journalistic’?

Yeah. Well, I mean I’ll give you another very clear example of a war where one side was absolutely wrong: the Nazis were totally wrong. I would rather read an account by someone who would raise an alarm in my head about who the Nazis are and what they’re doing. It’s an extreme case, but I’m using it as an example. I would much rather read a writer I trust for whatever reasons to tell me what’s happening, instead of saying: Okay, this is what they are saying, that the Nazis kill Jews and this and that, but the Nazis are saying something else. You begin to muddy the waters when you go like this.

I am not saying there are no other sides to a story. There are. But I think it doesn’t mean each side has the same moral equivalence. They seldom do. What the Bosnian-Serbs were doing in Bosnia was outrageous. It doesn’t mean the Muslims didn’t commit atrocities. But certainly not as an overarching policy. An individual commander might have done some atrocities. But the Bosnian-Serb policy to expel people and kill them that’s wrong!

Isn’t it a thin and dangerous line to take one point of view? The Nazis are a very extreme example.

It ís different. I am going to do a comic at some point about the Serb side. It doesn’t mean that I agree with them, of course not. You can easily get lost in listening to what people have to say.

Another example: in Raffa, In Israel, there was a Palestinian demonstration and a helicopter fired and killed eight or nine demonstrators. Okay, that’s the fact. The Israeli government put out maybe four different stories of what could have happened. Okay, you can report these stories, but the problem… and maybe you should report them but I’d rather a journalist said: the Israelis are saying this but you have to put it in the context of what did happen.

Journalists can be manipulated because the American way of doing journalism is you are going to give the other guy a chance to say his piece. But you have to be careful. You have to look at it and ask yourself how much truth is in what they are telling you, rather than just reporting it like, Well, the Israelis say this.’

In The Fixer, however, you show yourself as full of doubts about what is true and what is not. That’s quite the opposite of your firm conviction of who are the good guys and the bad guys in Palestine and Gorazde.

Here’s the thing: let’s say I am sympathetic to the Palestinian side. It doesn’t mean that everything they tell me is the truth. You have to be careful with what they say. My thing is to present an accurate, honest picture. I might be sympathetic to the cause but it doesn’t mean I agree with everything they do, their tactics and so on. So yeah, in the Fixer I wanted to show more the fact that you can get manipulated even by people who you might otherwise want to agree with. It’s the first book where I am really trying to express that.

You write somewhere that Neven, the central character in The Fixer, made you feel like a teenage boy on a first date.

I didn’t know what I was doing at some point when I was in Serbia. It was a strange place to be and I felt unsure of myself. In some ways you feel kind of comfortable with a person like that, he represents something to you. When you feel a little powerless or vulnerable there’s an attraction to someone who is powerful.

You seem naive at times as well

I was very naive.

You make yourself very small in The Fixer.

These were my first days in Sarajevo. I was a little scared.

At a certain moment in the book Neven says he’d like to murder a journalist who looks like him to take his passport and go to another country. You keep seeking his company after that, though.

Well, I did think it was objectionable. Neven seemed pretty much like a loose canon sometimes. But he was still around and I ran into him from time to time. Yeah, it was scary. But even then, much of what he said was just bullshit. So much of what he said was kind of ridiculous. I was already stepping back from him. The reason I went to see him was he said he wanted to have his tape recorder back or he said he did.

How do other journalists regard you?

The journalists I know like my work. I’ve worked with some of them. In certain situations journalists are your best friends. If anything is going to happen to you they are the ones who will try to help you out. If anyone of us would be captured, all the others would write about it, just to bring attention to it. One of my friends, a Turkish journalist, made a big stink when a Turkish journalist was captured by the Serbs and Nato wasn’t paying attention to it. Other journalist joined in and they had to do something about it, they had to act because of all the publicity.

Is your approach criticised by other journalists?

I am not pretending that I am doing what they’re doing. They try to write something they consider objective or that qualifies to standard American journalism. But it’s clear I have a point of view. There’s an element of opinion in my work.

Does the comic form give you any liberties that other journalists don’t have?

Not that I am aware of. There are writers like Robert Fisk who write in the first person and who write exactly what they feel. Fisk reports from Iraq, he’s highly critical of what the Americans are doing and he is unafraid to sort of look at things and to connect the dots.

Does the comic form give you any advantages? I know a disadvantage: it takes more time.

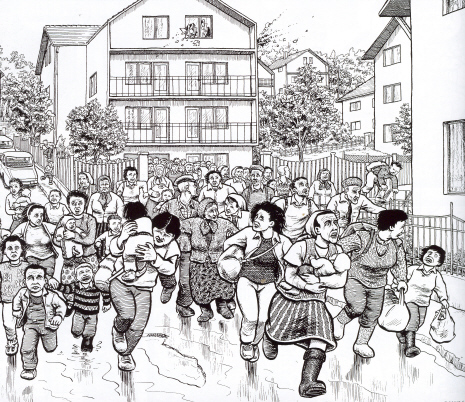

That’s definitely a disadvantage. An advantage is it becomes more immediate for the reader. I can draw what a place looks like and feels like. And so the reader opens it up and he’s in the streets of Gorazde or in the Gaza Strip. A lot of things a writer can mention once, like that it’s muddy in Gaza. In a comic these are repeated images. You can draw them over and over again. So it’s just present all the time, almost in a subconscious way. It really sinks in that it’s muddy everywhere. It’s hard to do those things in prose. You can’t keep alerting the reader to those things in prose without being really awkward.

In Palestine you are very critical of the Israelis. Have you spoken to Israeli people about that?

I am sure some Israelis or Jewish people would get upset by what I have done. They basically just don’t agree with my assessment of things. That’s fine.

Americans don’t have a reputation of being overly interested in foreign affairs. Do your books sell at all in the US?

The book sells surprisingly well. Palestine does well. It didn’t when it was coming out as a comic. It did terribly. Between thirteen hundred and fifteen hundred copies were sold. It did pretty bad. It wasn’t making anyone any money. When it was collected into a book it began to sell pretty well. I think over twenty thousand copies. The first print of The Fixer I think sold out, nine thousand copies.

Do you censor yourself?

No, I edit, I keep out irrelevant stuff. If I think they’re exaggerating or anything. The next book I am doing I go into the problems of exaggerations, of how memory warps things. It’s about Gaza, some historical incident seen through the eyes of sixty old men. I am trying to see if it’s possible to filter out a conclusion, to tell what actually happened, relying on these witnesses, who are not telling the exact truth. I am trying to judge my own view too.

How do people you interview react to the fact that you present yourself a comic author?

Generally they react pretty well. When I was talking to these old men I showed them the book about Palestine. The great thing about it being a comic book is they open it up they see get it right away: this is Gaza, this is where we live. The Palestinians have a great cartoonist called Nagel Ali, who was assassinated in London in the eighties. He criticised the Israelis, the PLO. I didn’t tell everyone I was doing comics, but people had his picture on their walls. But people want to talk about their experiences anyway, even if they don’t believe it’s going to help at all.

Now that you are a well respected comics journalist, is it easier for you now to get visas and stuff?

Yes. Big magazines give me press passes now; I had a New York Times press card. It’s getting better at that level. There’s more credibility, more respect.

Many thanks to Geert de Weyer.

English, Peter Breedveld, strips, 12.02.2005 @ 09:57

RSS

RSS